I watched the movie, Green Book, recently.

I usually avoid feel-good movies that minimize and/or trivialize black suffering. I watched this movie, however, because I wanted to support the efforts of the Luther College Student Activities Council and Black Student Union. I’m a faculty member at Luther College, and these two organizations co-sponsored a showing of the film followed by a discussion.

During the discussion, I expressed my disappointment and frustration with the film. I stated that there was so much the film could have but failed to explore with regards to racism.

The film tells the story of an unlikely but apparent friendship between the relatively unknown musical prodigy, composer, and virtuoso pianist, Donald Shirley, and Tony Vallelonga, a working-class Italian-American from the Bronx who was hired to chauffeur Shirley on a 1962 tour of the Jim Crow South.

The film’s approach to race and racism (especially during the 1960s) is naive, simplistic, and ill-informed. While there were multiple opportunities to engage in a more complex and nuanced examination of race, the film failed at virtually every turn.

In response to my critique, one person stated that there simply was not enough time to do everything. This, of course, is true. Movies cannot explore everything. Producers, directors, and screenplay writers have to make decisions regarding what they want to prioritize. The film’s failure, however, to engage in a more complex and nuanced examination of race and racism was not the result of a lack of time; it was the result of a lack of priority.

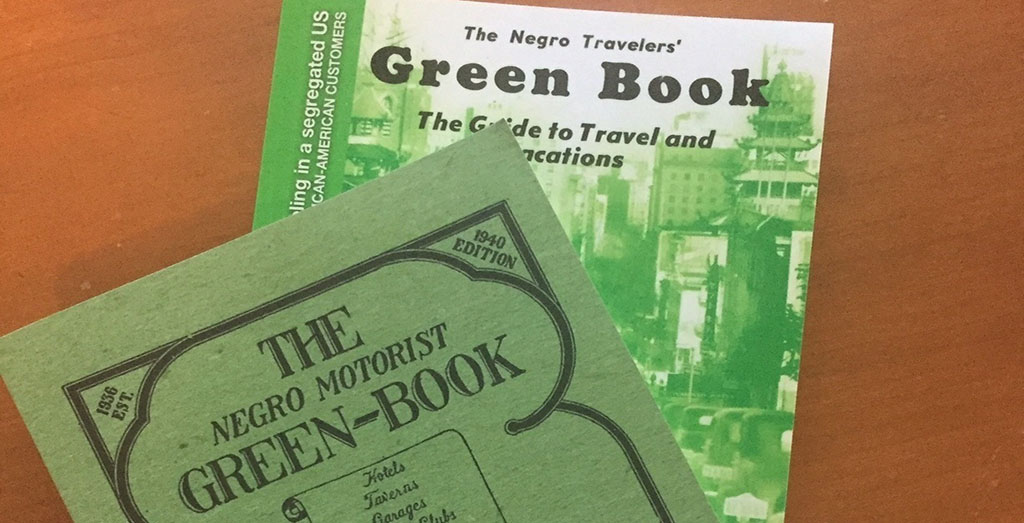

The film did not explore the damaging and pernicious effects of institutionalized racism, the complex and complicated life of Donald Shirley, nor the importance of a traveler’s guide known as The Green Book because none of these issues were a priority. They were not the film’s focus.

The focus of the film was on telling the story of the transformation of a white man from a racist bigot to a heroic white savior. Foregrounding this transformation came at the expense of reducing to a supporting role the extraordinarily complex, complicated, and amazing life of Donald Shirley. It also came at the expense of trivializing the importance for black people of the travel guide after which the film is named.

While the bulk of the film takes place within the context of Shirley’s tour of the Jim Crow South, the actual reason for the tour contributes little to the film’s storyline. The film makes a passing reference to the brutal onstage assault against Nat King Cole in Birmingham, AL six years earlier. King swore he would never return to the segregated South. Shirley undertook his tour of whites-only theaters and parlor venues out of civic obligation — and stubbornness. The tour represented Shirley’s response to and protest against structural Jim Crow racism.

While Green Book could have been an amazing film committed to highlighting the story of Donald Shirley and Tony Vallelonga confronting the pernicious effects of structural racism, instead it marked an unwelcome return of the “cute racism movie.”

The cute racism movie is a genre of film that offers predominantly white audiences the comforting sense that structural racism is a thing of the past and personal racism can be eradicated by black and white people getting to know one another and realizing that “we’re all the same.”

While I have always found this tone-deaf approach to racism appalling, what makes Green Book even more egregious is that it takes its title from a travel guide that was an indispensable resource designed for helping black people navigate and survive in a violently racist and segregated nation and it never explores the significance of that resource.

In the era of Jim Crow segregation, institutionalized racism presented serious dangers for black travelers. For black travelers, The Green Book was a tool of survival. It was written and published by a retired African American postal carrier named Victor Green.

The first edition was published in 1936. The introduction of the 1948 edition of the book ended,

There will be a day sometime in the near future when this guide will not have to be published. That is when we as a race will have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States. It will be a great day for us to suspend this publication for then we can go wherever we please, and without embarrassment.

The final edition was published in 1966. For thirty years The Green Book provided a safety net for black travelers warning them of sundown towns and racially hostile establishments to avoid.

While the book was no longer published after 1966, the historic events of 1968 and the continued existence of racial disparities today reveal that Black Americans as a people still do not “have equal opportunities and privileges in the United States.” The film, of course, has no interest in speaking to this reality.

The movie could have easily told its simplistic story of racial friendship between Tony and Donald and the transformation of Tony from bigot to savior without trivializing one of the most important resources committed to protecting traveling black people from white terrorism.

In their first “Green Book” location stop–an apparently run-down Carver Courts Motel–Tony responds to The Green Book entry describing the place as offering the comforts of home by saying, this place “looks like my ass.”

It is obvious that the movie is not concerned with accurately depicting The Green Book nor seriously exploring the complex and painful realities of racism in America during the brutally violent segregated Jim Crow period. The filmmakers, therefore, should have refrained from using Green Book as the title of a film that utterly disrespects the valuable contributions of The Green Book.

This movie’s disregard and blatant trivialization of The Green Book in order to tell a cute racism story focused on the transformation of a white racist is an insult to black people in America who were forced to rely on The Green Book and on their own ingenuity, resilience and courage in order to survive in the face of irrational yet fiercely defended racial bigotry and terrorism.

When I communicated with my mother after watching the film, she reminded me of stories about her parents packing enough food and drinks for their entire trips. Since there were no rest areas they could use, her father would occasionally pull off to the side of the road when they drove during the night in order to take a nap. As a child, my mom was always too scared to sleep, and she was always glad when her father would wake up and start driving again.

When she and her siblings had to go to the restroom, they would pull over to the side of the road and my grandmother would open the front and back doors on the passenger side to protect their privacy while they did what they had to do on the side of the road. They were unable to stop at most service stations to use the so-called “public” restrooms.

My mom told me that at that time, she never knew why they had to travel that way. She thought it was normal and the way all people traveled. She only realized as she got older that it was the way black people were forced to travel in America. It was part of what “driving while black” meant in Jim Crow America. While the hardships of “driving while black” are slightly different today, they are no less dangerous.

While it is often said, “art imitates life,” I hope Green Book’s selection as the Academy Award’s 2019 Best Picture does not mean most Americans have bought into the naive and ill-informed view that structural racism is a thing of the past and that building a genuinely antiracist society can be achieved simply by becoming friends with one person of another race. This was not the case in 1962 and it is certainly not the case today.

Leave a Comment